Contents

| « Prev | Kingo’s Childhood and Youth | Next » |

Chapter Three Kingo’s Childhood and Youth

Thomas Kingo, the first of the great Danish hymnwriters, grew forth as a root out of dry ground. There was nothing in the religious and secular life of the times to foreshadow the appearance of one of the great hymnwriters, not only of Denmark but of the world.

The latter part of the 16th and the first half of the 17th centuries mark a rather barren period in the religious and cultural life of Denmark. The spiritual ferment of the Reformation had subsided into a staid and uniform Lutheran orthodoxy. Jesper Brochman, a bishop of Sjælland and the most famous theologian of that age, praised king Christian IV for “the zeal with which from the beginning of his reign he had exerted himself to make all his subjects think and talk alike about divine things”. That the foremost leader of the church thus should recommend an effort to impose uniformity upon the church by governmental action proves to what extent church life had become stagnant. Nor did such secular culture as there was present a better picture. The Reformation had uprooted much of the cultural life that had grown up during the long period of Catholic supremacy, but had produced no adequate substitute. Even the once refreshing springs of the folk-sings had dried up. Writers were laboriously endeavoring to master the newer and more artistic forms of poetry introduced from other countries, but when the forms had been achieved the spirit had often fled, leaving only an empty shell. Of all that was written during these years only one song of any consequence, “Denmark’s Lovely Fields and Meadows”, has survived.

Against this bleak background the work of Kingo stands out 22 as an amazing achievement. Leaping all the impediments of an undeveloped language and an equally undeveloped form, Danish poetry by one miraculous sweep attained a perfection which later ages have scarcely surpassed.

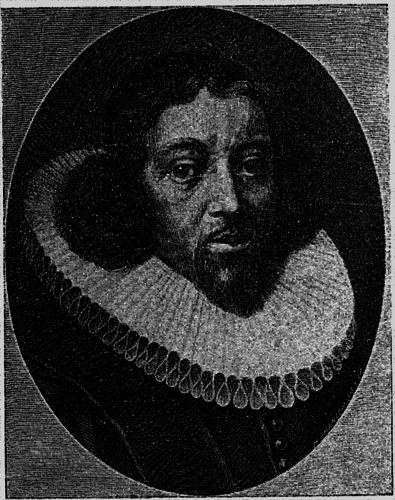

Thomas Kingo

Of this accomplishment, Grundtvig wrote two hundred years later: “Kingo’s hymns represent not only the greatest miracle of the 17th century but such an exceptional phenomenon in the realm of poetry that it is explainable only by the fates who in their wisdom preserved the seed of an Easter Lily for a thousand years, and then returned it across the sea that it might flower in its original soil”. Kingo’s family on the paternal side had immigrated to Denmark from that part of Scotland which once had been settled by the poetic Northern sea rovers, and Grundtvig thus conceives the poetic genius of Kingo to be a revival of an ancestral gift, brought about by the return of his family to its original home and a new infusion of pure Northern blood. The conception, like so much that Grundtvig wrote is at least ingenious, and it is recommended 23 by the fact that Kingo’s poetry does convey a spirit of robust realism that is far more characteristic of the age of the Vikings than of his own.

Thomas Kingo, the grandfather of the poet, immigrated from Crail, Scotland, to Denmark about 1590, and settled at Helsingør, Sjælland, where he worked as a tapestry weaver. He seems to have attained a position of some prominence, and it is related that King James IV of Scotland, during a visit to Helsingør, lodged at his home. His son, Hans Thomeson Kingo, who was about two years old when the family arrived in Denmark, does not appear to have prospered as well as his father. He learned the trade of linen and damask weaving, and established a modest business of his own at Slangerup, a town in the northern part of Sjælland and close to the famous royal castle of Frederiksborg. At the age of thirty-eight he married a young peasant girl, Karen Sørendatter, and built a modest but eminently respectable home. In this home, Thomas Kingo, the future hymnwriter, was born December 15, 1634.

It was an unusually cold and unfriendly world that greeted the advent of the coming poet. The winter of his birth was long remembered as one of the hardest ever experienced in Denmark. The country’s unsuccessful participation in the Thirty Year’s War had brought on a depression that threatened its very existence as a nation; and a terrible pestilence followed by new wars increased and prolonged the general misery, making the years of Kingo’s childhood and youth one of the darkest periods in Danish history.

But although these conditions brought sorrow and ruin to thousands, even among the wealthy, the humble home of the Kingos somehow managed to survive. Beneath its roof industry and frugality worked hand in hand with piety and mutual love to brave the storms that wrecked so many and apparently far stronger establishments. Kingo always speaks with the greatest respect and gratitude of his “poor but honest parents”. In a poetic description of his childhood years he vividly recalls their indulgent kindness to him.

|

But discipline was not forgotten. Parents in those days usually kept the rod close to the apple, often too close. And Kingo’s parents, despite their kindness, made no exception to the rule. He was a lively, headstrong boy in need of a firm hand, and the hand was not wanting.

|

he wrote later, adding that the fruits of that chastisement are now sweet to him. Nor do his parents ever appear to have treated him with the cold, almost loveless austerity that so many elders frequently felt it their duty to adopt toward their children. Their discipline was tempered by kindness and an earnest Christian faith. Although Hans Kingo seems to some extent to have been influenced by the strict Presbyterianism of his Scotch forebears, he does not appear, like so many followers of that stern faith, to have taught his children to believe in God as the strict judge rather than as the loving Father of Jesus Christ. In his later years the son at least gives us an attractive picture of his childhood faith:

|

These bright years of his happy childhood were somewhat darkened, however, when, at the age of six, he entered the Danish and, two years later, the Latin school of his home town. Nothing could be more unsuited for a child of tender years than the average school of those days. The curriculum was meager, the teaching poor and the discipline cruel. Every day saw its whipping scenes. For a day’s unexplained absence the punishment for the smaller boys was three lashes on their bare seats and for the larger an equal number on their bare backs. For graver offences up to twenty lashes might be administered. On entering the Latin school every boy had to adopt a new language. Only Latin could be spoken within its classical confines; and woe be to the tike who so far forgot himself as to speak a word in the native tongue anywhere upon the school premises. The only way anyone, discovered to have perpetrated such a crime, could escape the severest punishment was to report another culprit guilty of the same offense. Under such conditions one cannot wonder that Kingo complains:

25

|

At the age of fifteen Kingo, for reasons now unknown, was transferred from the school of his home town to that at the neighboring city of Hillerød. Here, on account of his outstanding ability, he was accepted into the home of his new rector, Albert Bartholin, a young man of distinguished family and conspicuous personal endowments.

Although the school at Hillerød was larger, it probably was not much better than that at Slangerup; but the close association of the humble weaver’s son with his distinguished rector and his refined family, no doubt, was a distinct advantage to him. The location of Hillerød on the shores of the idyllic Frederiksborg Lake and close to the magnificent castle of the same name is one of the loveliest in Denmark. The castle had recently been rebuilt, and presented, together with its lovely surroundings, a most entrancing spectacle. Its famous builder, Christian IV, had just gone the way of all flesh; but the new king, Frederik, known for his fondness for royal pomp, frequently resided at the castle together with his court, and thus Kingo must often have enjoyed the opportunity to see both the king and the outstanding men of his government.

It is not unlikely that this near view of the beauty and splendor of his country, the finest that Denmark had to offer, served to awaken in Kingo that ardent love for all things Danish for which he is noticed. While still at Hillerød he, at any rate, commenced a comprehensive study of Danish literature, a most unusual thing for a young student to do at a time when German was the common language of all the upper classes and Danish was despised as the speech of traders and peasants. As neither his school nor the general sentiment of the intellectual classes did anything to encourage interest in native culture, some other influence must have aroused in the young Kingo what one of his early biographers calls “his peculiar inclination for his native tongue and Danish poetry”. A few patriotic and forward looking men, it is true, had risen above the general indifference and sought to inspire a greater interest in the use and cultivation of the Danish language; but this work was still very much in its infancy, and it is not likely that the young Kingo knew much about it.

He graduated from Hillerød in the spring of 1654, and enrolled 26 at the university of Copenhagen on May 6 of the same year. But a terrific outbreak of the plague forced the university to close on May 30, and Kingo returned to his home. The scourge raged for about eight months, carrying away one third of the city’s population, and it was winter before Kingo returned to the school and enrolled in the department of theology. The rules of the university required each student, at the beginning of his course, to choose a preceptor, a sort of guardian who should direct his charge in his studies and counsel him in his personal life and conduct. For this very important position Kingo wisely chose one of the most distinguished and respected teachers at the university, Prof. Bartholin, a brother of his former rector. Professor Bartholin was not only a learned man, known for his years of travel and study in foreign parts, but he was also a man of rare personal gifts and sincere piety. In his younger days he had spent four years at the castle of Rosenholm where the godly and scholarly nobleman, Holger Rosenkrans, then gathered groups of young nobles about him for study and meditation. Rosenkrans was a close friend of John Arndt, a leader in the early Pietist movement in Germany, to which the young Bartholin under his influence became deeply attached. Nor had this attachment lessened with the years. And Bartholin’s influence upon Kingo was so strong that the latter, when entering upon his own work, lost no time in showing his adherence to the Arndt-Rosenkrans view of Christianity.

Meanwhile he applied himself diligently to his work at the university. Like other disciplines the study of theology at that time was affected by a considerable portion of dry-rust. Orthodoxy ruled the cathedra. With that as a weapon, the student must be trained to meet all the wiles of the devil and perversions of the heretics. Its greatest Danish exponent, Jesper Brochman, had just passed to his reward, but his monumental work, The System of Danish Theology, remained after him, and continued to serve as an authoritative textbook for many years to come. Though dry and devoted to hairsplitting as orthodoxy no doubt was, it probably was not quite as lifeless as later generations represent it to have been. Kingo is often named “The Singer of Orthodoxy”, yet no one can read his soul-stirring hymns with their profound sense of sin and grace without feeling that he, at least, possessed a deeper knowledge of Christianity than a mere dogmatic training could give him.

Kingo’s last months at the university were disturbed by a new war with Sweden that for a while threatened the independent existence 27 of the country, a threat which was averted only by the ceding of some of its finest provinces. During these stirring events, Kingo had to prepare for his final examinations which he passed with highest honors in the spring of 1658.

Thus with considerable deprivation and sacrifice, the humble weaver’s son had attained his membership in the academic world, an unusual accomplishment for a man of his standing in those days. His good parents had reason to be proud of their promising and well educated son who now, after his many years of study, returned to the parental home. His stay there was short, however, for he obtained almost immediate employment as a private tutor, first with the family of Jørgen Sørensen, the overseer at Frederiksborg castle, and later, with the Baroness Lena Rud of Vedby Manor, a position which to an impecunious but ambitious young man like Kingo must have appeared especially desirable. Lena Rud belonged to what at that time was one of the wealthiest and most influential families in the country. Many of her relatives occupied neighboring estates, a circumstance which enabled Kingo to become personally acquainted with a number of them; and with one of them, the worthy Karsten Atke, he soon formed a close and lasting friendship. He also appears to have made a very favorable impression upon his influential patrons and, despite his subordinate position, to have become something of a social leader, especially among the younger members of the group.

Meanwhile the country once again had been plunged into a desperate struggle. The Swedish king, Gustav X, soon repented of the peace he had made when the whole country was apparently at his mercy, and renewed the war in the hope of affixing the Danish crown to his own. This hope vanished in the desperate battle of Copenhagen in 1659, where the Swedish army suffered a decisive defeat by the hand of an aroused citizenry. But detachments of the defeated army still occupied large sections of the country districts where they, like all armies of that day, robbed, pillaged and murdered at will, driving thousands of people away from their homes and forcing them to roam homeless and destitute through the wasted countryside. Acts of robbery and violence belonged to the order of the day. Even Kingo received a bullet through his mouth in a fight with a Swedish dragoon, whom he boldly attempted to stop from stealing one of his employer’s horses. When the country finally emerged from the conflict, her resources were depleted, her trade destroyed, and large sections of her country districts laid waste, losses which it required years for her to 28 regain. But youth must be served. Despite the gravity and hardships of the day, the young people from Vedby managed to have their parties and other youthful diversions. And at these, Kingo soon became a welcome and valued guest. His attractive personality, sprightly humor and distinct social gifts caused his highly placed friends to accept him with delight.

This popularity, if he had cared to exploit it, might have carried him far. In those days the usual road to fame and fortune for an obscure young man was to attach himself to some wealthy patron and acquire a position through him. With the aid of his wealthy friends Kingo could easily enough have obtained employment as a companion to some young noble going abroad for travel and study. It came, therefore, as a surprise to all when he accepted a call as assistant to the Reverend Jacobsen Worm at Kirkehelsinge, a country parish a few miles from Vedby. The position was so far short of what a young man of Kingo’s undoubted ability and excellent connections might have obtained, that one may well ask for his motive in accepting it. And although Kingo himself has left no direct explanation of his action, the following verses, which he is thought to have written about this time, may furnish a key.

|

It is understandable, at least, that a young man with such sentiments should forego the prospect of worldly honor for a chance to serve his Master.

Kingo was ordained in the Church of Our Lady at Copenhagen in September, 1661, and was installed in his new office a few weeks later. The seven years that he spent in the obscure parish were, no doubt, among the most fruitful years of Kingo’s life, proving the truth of the old adage that it is better that a man should confer honor on his position than that the position should confer honor upon him. His fiery, forceful eloquence made him 29 known as an exceptionally able and earnest pastor, and his literary work established his fame as one of the foremost Danish poets of his day.

While still at Vedby, Kingo had written a number of poems which, widely circulated in manuscripts, had gained him a local fame. But he now published a number of new works that attained nation-wide recognition. These latter works compare well with the best poetry of the period and contain passages that still may be read with interest. The style is vigorous, the imagery striking and at times beautiful, but the Danish language was too little cultivated and contemporary taste too uncertain to sustain a work of consistent excellence. Most successful of Kingo’s early poems are “Karsten Atke’s Farewell to Lion County”, a truly felt and finely expressed greeting to his friends, the Atkes, on their departure from their former home, and “Chrysillis”, a lovesong, written in a popular French style that was then very much admired in Denmark. Both poems contain parts that are surprisingly fine, and they attained an immense popularity. But although Kingo throughout his life continued to write secular poetry that won him the highest praise, that part of his work is now well nigh forgotten. It is truly interesting to compare the faded beauty of his secular poems with the perennial freshness of his hymns.

It was inevitable that Kingo, with his high ambitions and undoubted ability should desire a larger field of labor. His salary was so small that he had to live in the home of his employer, a circumstance that for various reasons was not always pleasant. Pastor Worm had married thrice and had a large family of children of all ages from a babe in arms to a son at the university. This son, Jacob Worm, was a brilliant but irascible and excessively proud youth only a few years younger than Kingo. From what we know about him in later years, it is likely that Kingo’s contact with him during his vacations at home must have proved exceedingly trying. The bitter enmity that later existed between the two men probably had its inception at this time. In 1666, Kingo, therefore, applied for a waiting appointment to his home church at Slangerup, where the pastor was growing old and, in the course of nature, could be expected ere long to be called to his reward. The application was granted, and when the pastor did die two years later, Kingo at once was installed as his successor.

Slangerup was only a small city, but it had a new and very beautiful church, which still stands almost unchanged. One may still sit in the same pews and see the same elaborately carved 30 pulpit and altar which graced its lofty chancel during the pastorate of the great hymnwriter. A beautiful chandelier, which he donated and inscribed, still adorns the arched nave. In this splendid sanctuary it must have been inspiring to listen to the known eloquence of its most famous pastor as he preached the gospel or, with his fine musical voice, chanted the liturgy before the altar. The church was always well attended when Kingo conducted the service. People soon recognized his exceptional ability and showed their appreciation of his devoted ministry. The position of a pastor was then much more prominent than it is now. He was the official head of numerous enterprises, both spiritual and civic, and the social equal of the best people in the community. With many people the custom of calling him “Father” was then by no means an empty phrase. Parishioners sought their pastor and accepted his counsel in numerous affairs that are now considered to be outside of his domain. In view of Kingo’s humble antecedents, a position of such prominence might well have proved difficult to maintain among a people that knew his former station. But of such difficulties the record of his pastorate gives no indication. He was, it appears, one exception to the rule that a prophet is not respected in his own country.

When he moved to Slangerup, Kingo was still unmarried. But about two years later he married the widow of his former superior, Pastor Worm, becoming at once the head of a large family consisting of the children of his wife and those of her first husband by his previous marriage. It was a serious responsibility to assume, both morally and financially. The parish was quite large, but his income was considerably reduced by the payment of a pension to the widow of the former pastor and the salary to an assistant. With such a drain on his income and with a large family to support, Kingo’s economic circumstances must have been strained. But he was happy with his wife and proved himself a kind and conscientious stepfather to her children who, even after their maturity, maintained a close relationship with him.

Kingo’s happiness proved, however, to be but a brief interlude to a period of intense sorrows and disappointments. His wife died less than a year after their marriage; his father, whom he loved and revered, passed away the same year; and the conduct of his stepson, the formerly mentioned Jacob Worm, caused him bitter trouble and humiliation. The bright prospect of this brilliant but erratic youth had quickly faded. After a number of failures, he had been forced to accept a position as rector of the small and insignificant 31 Latin school at Slangerup, thus coming under the immediate authority of Kingo, who, as pastor, supervised the educational institutions of the parish. Worm always seems to have thought of Kingo as a former assistant to his father, and his position as an inferior to a former inferior in his own home, therefore, bitterly wounded his pride. Seeking an outlet for his bitterness, he wrote a number of extremely abusive poems about his stepfather and circulated them among the people of the parish. This unwarranted abuse aroused the anger of Kingo and provoked him to answer in kind. The ensuing battle of vituperation and name-calling brought no honor to either side. Worm’s conduct toward his superior, the man who was unselfishly caring for his minor sisters and brothers, deserves nothing but condemnation; but it is painful, nevertheless, to behold the great hymnwriter himself employing the abusive language of his worthless opponent. The times were violent, however, and Kingo possessed his share of their temper. Kingo’s last act in this drama between himself and his stepson throws a somewhat softening light upon his conduct. Embittered by persistent failures, Worm continued to pour out his bitterness not only upon his stepfather, but upon other and much higher placed persons until at last he was caught and sentenced to die on the gallows for “having written and circulated grossly defamatory poems about the royal family”. In this extremity, he appealed to Kingo, who successfully exerted his then great influence to have the sentence commuted to banishment for life to the Danish colony in India.

| « Prev | Kingo’s Childhood and Youth | Next » |